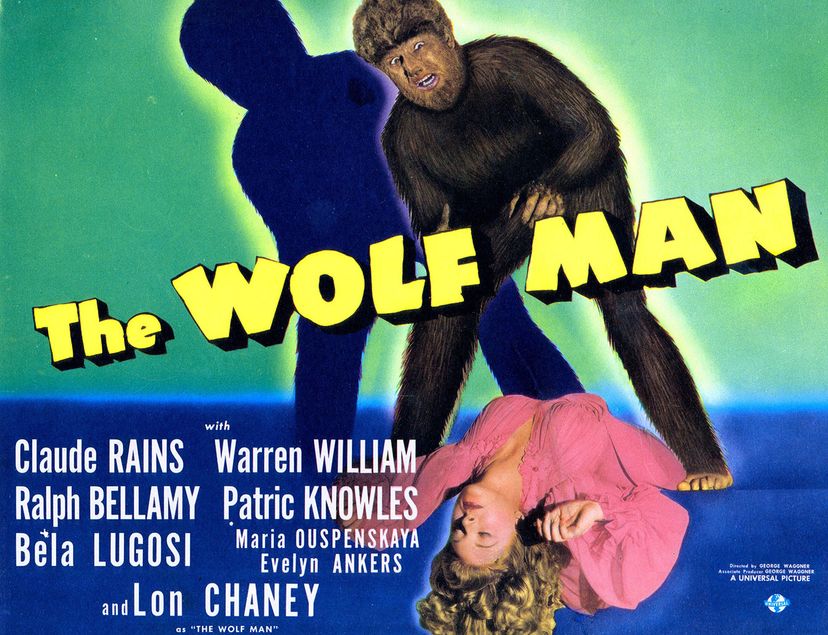

Many works of literature don't spend a lot of time describing what happens when a person becomes a wolf. One minute, a man is human. The next minute, he isn't. Even in movies like "The Wolf Man," the transformation process happens largely off-screen — the man himself, rather than his process of transformation, is the primary focus of the film.

At the same time, the werewolf transformation in "The Wolf Man" is convincing, particularly considering when the film came out. First, hair begins to grow from Larry Talbot's skin, and eventually, he becomes a creature that resembles a very hairy man with claws and fangs.

In more recent films, though, the process of becoming a wolf is often the highlight of the show. It appears in great detail, and it's often a painful experience.

Bones forcibly elongate and change their shape, sometimes moving so drastically that they rupture a person's skin. From beginning to end, the transformation can take several minutes, and the end result is a creature that is part human and part wolf, in varying proportions. Depending on the special effects available at the time of the film — and the techniques used to create them — these transformations can range from absurd to grotesque to truly convincing.

Whether a werewolf transforms when he dies varies from book to book and movie to movie. Sometimes, if a werewolf dies in wolf form, he remains a wolf forever. But in other depictions, he immediately reverts to his human form.

In these films, if you cut off a werewolf's paw, it can become a human hand before your eyes. In general, injuries sustained in wolf form appear on the werewolf's human body, making it much easier to determine which friend or neighbor is a lycanthrope.

In most modern portrayals, the only cure for lycanthropy is a silver bullet. But sometimes, potions, medicines or rituals can stop the transformation or at least keep it under control. In the "Harry Potter" books, Remus Lupin can sleep off his time as a werewolf if he drinks a wolfsbane potion. In the movie "Ginger Snaps," an injected infusion of monkshood can cure lycanthropy.

The Good Werewolves

In many depictions, these bloodthirsty beasts are evil — they kill animals and innocent people, sometimes for fun. But in some books and films, werewolves are good, or at least sympathetic. They stir the audience's compassion, largely because of their struggles to accept or control their lycanthropy.

This isn't entirely a recent invention. The story "Eena" by Manly Banister — published in 1947 — broke with tradition by portraying a werewolf who is both sympathetic and female. Other characters, like J.K. Rowling's Remus Lupin, seem to be entirely benevolent. One werewolf, the impenetrable Oz from "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," learns to control his lycanthropic impulses so he can be a better person and win back the heart of his ex-girlfriend, Willow.