It's how mountains form, volcanoes erupt and continents drift apart. So, what causes the tectonic plates to move? Discover the origins of the continental drift theory and how scientists explain these geologic phenomena.

Advertisement

It's how mountains form, volcanoes erupt and continents drift apart. So, what causes the tectonic plates to move? Discover the origins of the continental drift theory and how scientists explain these geologic phenomena.

Advertisement

Back in 1911, a German meteorologist and geophysicist named Alfred Wegener was doing research at a university library, when he came upon a scientific paper that listed ancient fossils of identical plants and animals that had been found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

This got Wegener to thinking about how the same organisms could have evolved in two places that were separated by thousands of miles of water.

Advertisement

Some scientists believed that land bridges had once existed between these places. But Wegener looked at maps of the coastlines of Africa and South America and came up with a different idea. What if those continents had once been joined together, and then moved apart, as part of a process that was still going on?

From that inspiration, Wegener came up with his theory of continental drift, which at the time was widely derided as ridiculous.

By the 1950s and 1960s, however, scientists had come around to thinking that Wegener might have been onto something, and that pieces of the Earth's crust are slowly moving — a process that not only explains many of the planet's features, but also may help make life on Earth possible.

Advertisement

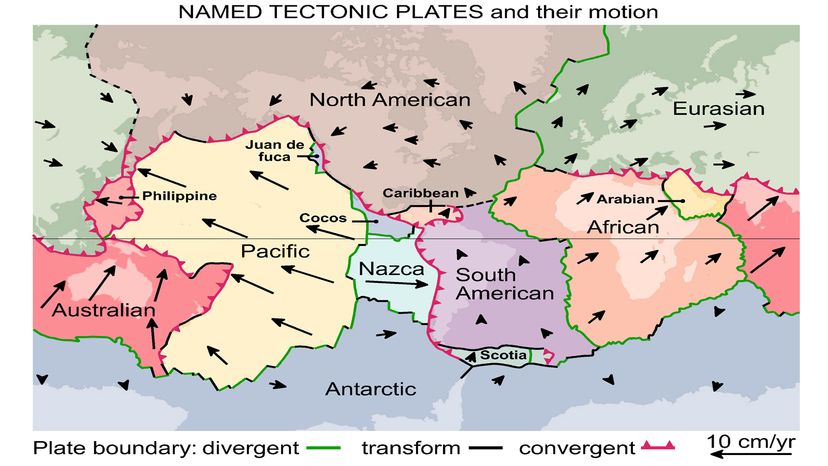

Plate tectonics is the theory that the Earth's crust and upper mantle are composed of numerous major and minor plates that fit together tightly but are in continuous motion, moving sometimes toward one another and other times apart.

The movement of plates is known as plate motion or tectonic shift, and it's been going on for a long, long time. A study by Johns Hopkins University researchers, published in August 2019, in the scientific journal Nature, concludes that plate tectonics began about 2.5 billion years ago, and has developed gradually since then.

Advertisement

"The Earth is a large-scale heat engine," Ray Russo, an associate professor of geology at the University of Florida and an expert in plate tectonics, explains via email.

"Heat left over from planetary accretion, from gravitational compression, and from radioactive decay is trapped in the Earth's interior. Because heat flows from warm to cold regions, the Earth's interior heat tends to flow toward its cold surface. The most efficient way for this heat to get from the deep interior to the Earth's surface is by convection. So, on a large scale, hot mantle material rises and replaces cold mantle material that has developed at Earth's surface.

"The cold material is, essentially, the Earth's rigid plates," Russo continues. "These plates become dense as they cool and eventually they become dense enough to sink into the mantle, cooling the planet and stirring the mantle on a global scale. In a nutshell, that's plate tectonics."

How does all this heat energy cause entire plates to move? One theory is slab pull. When dense oceanic plates sink below less-dense continental plates, they drag the rest of the plate with them, in a phenomenon known as slab pull.

The plates move really, really slowly — the average speed is 0.6 inches (1.5 centimeters) per year, though scientists have differing opinions on whether the movement is slowing down or increasing.

Advertisement

The plates interact along their boundaries in three different ways.

Where two plates move away from each other, there is a divergent boundary, a zone where earthquakes are common and hot magma, or molten rock, rises from the mantle to the surface to form new crust.

Advertisement

Conversely, in places where two plates come together, a convergent boundary occurs. The impact of the plates in those places can cause the edges to buckle and push up to form a mountain range, or else bend to create a deep trench in the ocean floor.

Chains of volcanoes often form parallel to the boundaries. Convergent boundaries create continental crust but destroy crust that's part of the ocean floor.

In a transform plate boundary, two plates slide past one another. Crust along a transform plate boundary will be cracked and broken, but unlike the other two types of boundaries, it won't create any new crust. Earthquakes are common along these faults.

Advertisement

As Russo explains, plate tectonics profoundly affect our entire planet and all of its natural processes. One big reason is that the movement of the plates causes the formation of volcanoes — basically, breaks in the crust that serve as vents for heat and lava — and their eruptions continually resurface the ocean basins that account for 72 percent of the Earth's surface.

Just as importantly, volcanic activity associated with tectonic plate movement causes lighter, less dense minerals to separate from the heavier, denser ones in the Earth's mantle. "The accumulation of these light minerals results in the development and growth of continents, on which we live," Russo says.

Advertisement

Tectonic plate movement also has helped to create, in numerous ways, the conditions that make life on Earth possible. It leads, for example, to the interaction of hot volcanic rocks with water in the ocean, and the leaching of ions from those rocks is what controls the oceans' salinity.

"Life evolved in the oceans, in the presence of this ion-rich water, and humans, for example, have blood salinity equivalent to the salinity of seawater as a direct consequence," Russo says.

Additionally, volcanic activity triggered by plate tectonics also has helped create the fertile soil that allows plants to grow and produce both food and the oxygen that sustains humans and large animal life, he notes.

By rearranging the configuration of the continents and the ocean basins, plate tectonics also influences the planet's climate. "For example, the current shapes of the ocean basins continually supply warm equatorial waters to polar regions, keeping the planet from developing very great extremes of surface temperature between equator and poles," Russo says.

The mountains formed by tectonics also are among the planet's most important carbon dioxide sinks, helping to draw down atmospheric C02 levels by forming new minerals. That process increases and decreases in response to shifts in temperature, enabling the mountains to act as giant thermostats.

The gradual shifting of the continental masses also has played an important role in biological evolution. "Speciation — the development of new species — occurs when a single group of plants or animals is divided into two groups that are no longer in reproductive contact, as, for example, often happens when a supercontinent breaks up and new ocean basins form between its continental fragments," Russo explains.

All this might make Alfred Wegener — who died in 1930, when he became lost in a blizzard while on an expedition in Greenland — feel vindicated at last.

Advertisement

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Advertisement