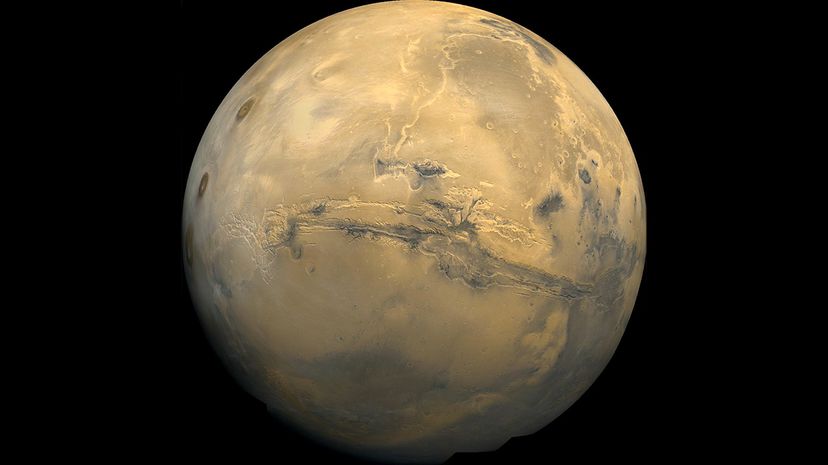

Martian landscape must be positively spellbinding. The red planet contains the solar system's largest volcano along with its biggest canyon. Scientists have named the latter "Valles Marineris." At 1,864 miles (3,000 kilometers) long and 372 miles (600 kilometers) across, it makes Earth's biggest canyons look like the cracks in a concrete driveway.

Mars is also notable for its so-called crustal dichotomy: The crust of the southern hemisphere has an average thickness of 36 miles (58 kilometers). Yet, that in the northern hemisphere is — again, on average — just 20 miles (32 kilometers) thick. Watters says this "contrast in topography" is reminiscent of the differences "between Earth's continents and ocean basins."

Could the disparity be the handiwork of plate tectonics? An Yin, a professor of geology at UCLA has written multiple papers about the surface of Mars. In 2012, he suggested that a Martian plateau called the Tharis Rise might've been made by a subduction zone — which is a place where one plate dives beneath another. That same year, he cited the Valles Marineris as a possible boundary area between two plates.

"They are hypotheses supported by what we know," Yin says via email, "but with more data to come in in the next couple of decades, things may change." For the moment, he's of the opinion that Mars has a primitive form of plate tectonics. However, even if this is true, Mars doesn't possess many plates. Also, plate-related activity on the red planet appears to progress at a much slower rate than it does on Earth.

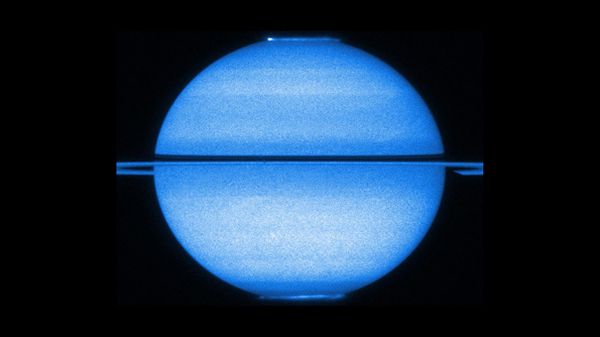

Now let's move on to one of our other celestial neighbors, shall we? The gassy atmosphere of Venus makes it a tough planet to survey. Still, we have learned a few things about its surface. "The present crust of Venus is relatively young," Watters says. Judging by some of the craters left behind by meteorites, its present-day surface is less than 1 billion years old.

Age isn't everything, though. Just like Earth, Venus has its own ridges, faults and (possibly active) volcanoes. A 2017 study argued that Venus owes much of its topography to prehistoric mantle plumes. These are columns of molten rock that sometimes reach a planet's crust. When they do, they often generate a "hot spot" of volcanic activity. Here on Earth, the lava released by mantle plumes created the Hawaiian Islands as well as Iceland.

In theory, the volcanic material unleashed by hot spots could explain the presence of coronae: large, oval-shaped structures found on Venus' surface. The plumes may have even led to the formation of unorthodox subduction zones around coronae rims. Not exactly plate tectonics, but still pretty neat.