The sea is primordial, vast and ever-changing, the source and destination of all waters. It advances and retreats with the tides. It gave rise to all life, yet its winds and waves bring death to the unwary or the unlucky. Given these connotations, it's small wonder that the sea plays such an essential role in so many cultures' creation myths, or that its gods and monsters rank among the most potent. To control the seas is to master chaos and to wield the power of creation and destruction [sources: Barré; Chevalier and Gheerbrant].

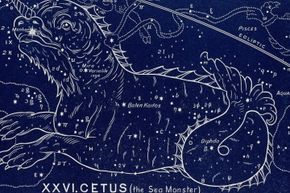

These oceanic associations spill over into the forms taken by sea gods, their servants and assorted briny beasts. The Mesopotamians saw their goddess Tiamat as a sea monster or many-headed dragon, an image that evokes the undulating power of waves, the force of floods or the destructive fury of tsunamis. Other deities, like the Greek sea god Poseidon, used monsters of the deep to visit their wrath upon mortal fleets and coastal cities. Still others demonstrated their might by destroying monstrous sea creatures, as God brought low Leviathan in the Old Testament.

Advertisement

Some psychoanalysts consider sea monsters, particularly the ones we imagine dwelling in the deepest ocean, as symbolizing the unconscious mind, which follows its own sinuous paths even while the surface mind seems placid. We mirror the capriciousness of nature in our own protean natures, and we project our fears of both onto the outside world [source: Haven].

Another reason for our belief in sea monsters is summed up by Jules Verne in his 1870 novel "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea": "Either we do know all the varieties of beings which people our planet, or we do not. If we do not know them all -- if Nature has still secrets in the deeps for us, nothing is more conformable to reason than to admit the existence of fishes, or cetaceans of other kinds, or even of new species ..."

The unknown invites us to populate it with creatures of our own invention, and vice versa: If we believe in undiscovered or unconfirmed creatures, we naturally imagine they live in inaccessible climes, be they high in the Himalayas, deep within an unexplored jungle -- or far below the all-concealing waves.

Whatever the reasons, most seafaring cultures have sea monster myths or folktales. They are preserved in manuscripts, in the margins of old maps, on the walls of Hindu temples and in the rock carvings of American Indians [source: Morell].

But is there a drop of truth to any of these tall tales? And how might we find out?

Advertisement