If you're worried about a killer limnic eruption breaking out in Lake Superior or Loch Ness, University of Michigan geoscience professor Youxue Zhang says you shouldn't be. The two most recent limnic eruptions were the Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun cataclysms that we've just described. Both bodies of water are located just above the equator, where it tends to be warm all year round.

There's just no way for a limnic eruption to happen in a temperate body of water. In places where seasonal temperatures vary wildly (like the Great Lakes), lake surfaces often cool down, causing the water at that level to sink and swap places with the layers of water beneath it. "Temperate lakes experience turnovers yearly, [so] it is not expected that any gas would be able to accumulate in lake bottom water," Zhang says via email. "Without [dissolved] gas accumulation, there would be no lake eruptions."

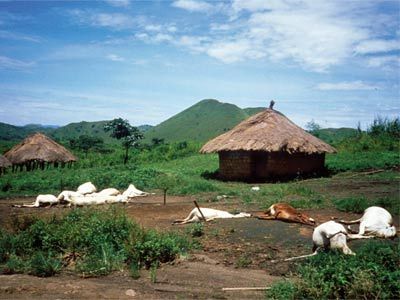

However, Zhang and many of his colleague have taken a healthy interest in Lake Kivu, a 1,042-square mile (2,700-square kilometer), up-and-coming vacation destination on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Why? Because it seems to have all the necessary criteria for a truly colossal limnic eruption.

There are about 10.5 billion cubic feet (300 million cubic meters) of dissolved CO2 and 2.1 billion cubic feet (60 million cubic meters) of methane lurking near the bottom. Were those gases to explode from the lake's surface, the 2 million people who live around Kivu might find themselves in jeopardy.

One possible solution: Harvest those very gases as a possible energy source by an extraction barge. KivuWatt is a one-of-a-kind $200 million facility that uses an offshore barge to draw up water from the lake. It then siphons off the methane and sends it to a power plant generating electricity for the area. When life gives you lemons, turn it into electricity.