Eventually, we will run out of oil. It takes at least 10 million years, specific geological processes and a mass extinction of dinosaurs and other ancient creatures to create crude oil -- making it the definition of a nonrenewable resource. But it's impossible to tell exactly when we will run out of oil, since we can't look into the Earth's mantle to see just how much is left.

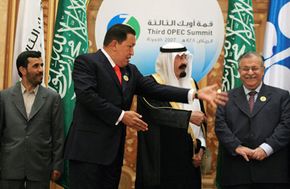

The oil company BP said that we've got plenty of oil left, according to its Statistical Review of World Energy published in June 2008. In the report, the company said that the world has as many as 1,238 billion barrels of oil in proved reserves [source: BP]. This equals about 40 years of uninterrupted oil supply -- just from oil pumped from the ground and held in reserve alone. These data were compiled from reported reserves from nations around the globe and oil consortiums like OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries).

Advertisement

But BP's report invited a hail of criticism from oil industry observers, who waved off BP's data as unfounded. Specifically, the criticism comes because member countries of organizations like OPEC receive funding based on the amount of oil they hold in reserve. What's more, say critics, the figures reported by individual countries aren't audited by outside sources [source: U.S. Government Accountability Office]. In other words, member countries may have the opportunity and the motive to exaggerate the number of barrels of oil they have in reserve.

Pulling the last drop of oil on Earth from the ground may be a long way off by anyone's measure. There are a variety of oil sources that have been discovered and are not yet being exploited. There are also a number of undiscovered sources of oil that experts assume exist. A much more pressing concern is this: Will we continue to have enough oil?

The theory of peak oil -- the point at which the Earth's oil supply begins to dwindle -- has become a hot-button topic in recent years. At this point, production of oil no longer continues the upswing that helped create the modern world as we know it. Instead, the upswing becomes a downturn. And if demand continues to grow while production begins to decline, we have a problem.

The basis for the concept of peak oil comes from a graph produced by Shell Oil geologist M. King Hubbert in the 1950s. The graph shows that oil reservoirs follow a predictable trajectory from discovery to depletion. Once oil is discovered, production from the reservoir continues to increase until it reaches its maximum output. After that, production plateaus, then begins to decline. Once it declines, production continues downward until the reservoir is depleted.

The Earth's combined oil supply should follow this bell curve, and the point where it begins to decline forever is the oil peak. This point will come eventually, since oil is nonrenewable. But exactly how long we have until that happens is a matter of heated debate. In this article, we'll look at what factors influence peak oil, what effects peak oil could have on people and some arguments against the theory. Read the next page to find out how peak oil works.

Advertisement