If you know what a black hole is, you're probably aware that it can contain as much mass as billions of stars, compressed into a much smaller space, and have such a powerful gravitational pull that even light can't escape its grasp.

But even though it's not possible to see into a black hole, it is possible to see light that's coming from behind one. In a paper published July 28, 2021, in the scientific journal Nature, researchers from Stanford University, Penn State University and Netherlands Institute for Space Research (SRON) describe the first-ever observation of light apparently being emitted from the far side of a supermassive black hole located in I Zwicky 1, a galaxy 800 million light-years away from Earth.

Advertisement

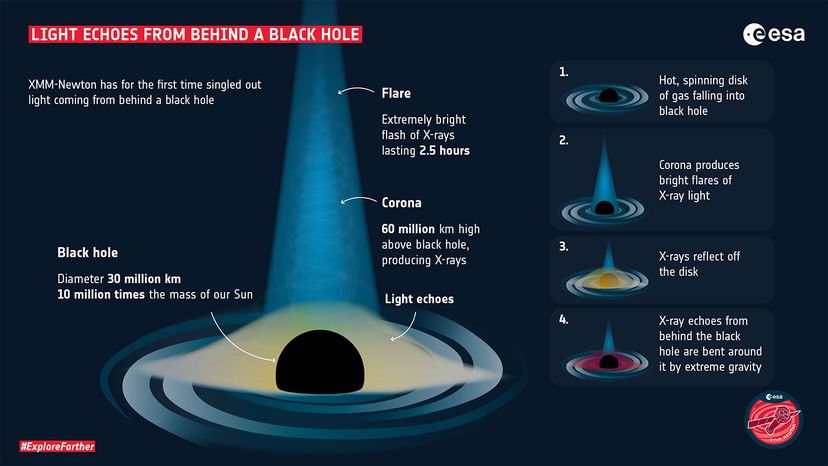

The researchers used European Space Agency's (ESA) XMM-Newton and NASA's NuSTAR space telescopes to take a look in the vicinity of a distant black hole, which has a diameter of 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) and contains about 10 million times the mass of our sun, according the ESA website.

During that work, the team's lead researcher, Stanford University astrophysicist Dan Wilkins, observed bright flares of X-rays coming from gas falling into the black hole, according to a Stanford news release. But then he noticed something unexpected — small flashes of X-rays that were different in "color," the term used to describe intensity.

The pattern of the flashes indicated that X-rays were being reflected from behind the black hole, as the supermassive object warped space-time and bent light — a phenomenon that was predicted by theoretical physicist Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity (AKA general relativity), published back in 1915, but which up to this point never actually had been confirmed.

"Any light that goes into that black hole doesn't come out, so we shouldn't be able to see anything that's behind the black hole," Wilkins, a research scientist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, explained in the news release.

It is another strange characteristic of the black hole, however, that makes this observation possible. "The reason we can see that is because that black hole is warping space, bending light and twisting magnetic fields around itself," Wilkins said.

While astrophysicists began speculating about how the magnetic field might behave close to a black hole many years ago, "they had no idea that one day we might have the techniques to observe this directly and see Einstein's general theory of relativity in action," another of the paper's co-authors, Stanford physic professor Roger Blandford, said in the release.

The researchers originally set out to study a different aspect of black holes. When gas is pulled into a supermassive black hole, it superheats to millions of degrees, causing electrons to separate from atoms and form a magnetized plasma that arcs high over the hole and twirls and breaks, in a way that resembles our sun's corona.

Scientists' effort to learn more black holes' coronas will continue, with the ESA's Athena (Advanced Telescope for High-ENergy Astrophysics) X-ray observatory as one of the tools.

Advertisement