UFO Crash Stories

The stories began to circulate in the late 1940s. They were so fantastic that even those willing to seriously consider the possibility of extraterrestrial visitation responded with incredulity.

In fact, no more than a couple of weeks after Kenneth Arnold's sighting ushered in the UFO age, the first such story hit the press. On the afternoon of July 8, 1947, a New Mexico paper, the Roswell Daily Record, startled the nation with a report of a flying saucer crash near Corona, Lincoln County, northwest of Roswell, and of the recovery of the wreckage by a party from the local Army Air Force base. Soon, however, the Air Force assured reporters that it had all been a silly mistake: The material was from a downed balloon.

Advertisement

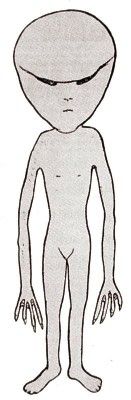

Though this particular incident was quickly forgotten, rumors of recovered saucers and, in addition, the bodies of their alien occupants, became a staple of popular culture -- and con games. In 1949 Variety columnist Frank Scully wrote that a "government scientist" and a Texas oilman had told him of three crashes in the Southwest. The following year Scully expanded these claims into a full-length, best-selling book, Behind the Flying Saucers, which claimed that the occupants of these vehicles were humanlike Venusians dressed in the "style of 1890." But two years later True magazine revealed in a scathing exposé that Scully's sources were two veteran confidence men, Silas Newton and Leo GeBauer. Newton and GeBauer were posing respectively as an oilman and a magnetics scientist in an attempt to set up a swindle involving oil-detection devices tied to extraterrestrial technology.

To serious ufologists, including those who suspected the government wasn't telling everything it knew about UFOs, crash stories were farfetched yarns of "little men in pickle jars." A person with such a story got a chilly reception when he or she passed it on to anyone but fringe ufologists. In 1952 Ed J. Sullivan of the Los Angeles-based Civilian Saucer Investigators wrote that such tales "are damned for the simple reason, that after years of circulation, not one soul has come forward with a single concrete fact to support the assertions. . . . We ask you to beware of the man who tells you that his friend knows the man with the pickle jar. There is good reason why he effects [sic] such an air of mystery, why he has been 'sworn to secrecy' -- because he can't produce the friend -- or the pickle jar."