"The Memory Trap," an espionage thriller by British author Anthony Price, contains this wry quote about airports: "The Devil himself had probably re-designed Hell in the light of the information he had gained from observing airport layouts." Whether you agree with Price or not (we suppose some people might find Heaven in the frenetic hub of their favorite airline), the observation captures the essence of the modern flying field: its complexity, its immensity and, of course, its density of people.

Any major airport has lots of customers, most of them passengers. For example, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport handles nearly 100 million passengers a year [source: Hartsfield-Jackson]. That's almost 20 times the number of people living in Atlanta itself and the same number of people living in a sizable country, say Ethiopia or Vietnam. Moving those people to their ultimate destinations requires 34 different airlines, which collectively make up the airport's 2,500 daily arrivals and departures. That's a lot of planes, a lot of passengers and a lot of airport personnel to make sure everything runs smoothly.

Advertisement

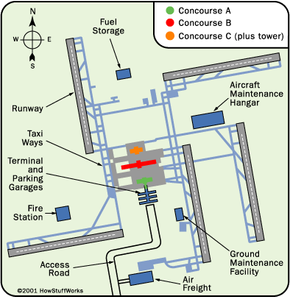

In many ways, a modern airport operates like a city. A governing body provides strategic direction and oversees day-to-day management. Waste removal crews collect trash from airport facilities and airplanes. Police and fire squads protect life and property. And various municipal-like departments handle administrative duties, ranging from human resources and public relations to legal and finance.

In addition to those activities, airports must also provide the resources necessary to care for a fleet of commercial aircraft. Airlines need space for airplanes, facilities for routine maintenance, jet fuel and places for passengers and flight crews while on the ground. Air-freight companies need space for loading and unloading cargo airplanes. And pilots and other crew members need runways, aircraft fuel, air traffic information, facilities for aircraft storage and maintenance, and places to relax while on the ground.

Throw in security concerns that arose after the Sept. 11 attacks, as well as capricious weather patterns, and you can see why job descriptions for airport managers often contain these kinds of descriptions: "You must have strong leadership and organizational skills, as well as excellent communication and interpersonal skills. This is not a position for the light-hearted and is stressful with long hours."

Luckily, our journey over the next few pages will give us a glimpse into the hidden world of airports without all of the attendant stress and nail-biting. Let's begin with a bird's-eye view.

Advertisement