Environmental Science

The environment is truly a thing of beauty and should be protected whenever possible. What can we do to save the environment, and what new technology is available to help us?

The Fish Doorbell Isn't a Joke ... Seriously

The Euphrates River, at the 'Cradle of Civilization,' Is Drying Up

Study Says 2035 Is Climate Change Point of No Return

9 Arctic Plants That Defy Nature to Bloom Near the North Pole

What State Has the Most Mountains in the U.S.? 8 Peak Records

The Most Dangerous Mountain to Climb (and 14 Giving Steep Competition)

How Many Birds Are Killed by Wind Turbines, Really?

How a Lithium Mine Works and Impacts Local Communities

How to Sell Electricity Back to the Grid

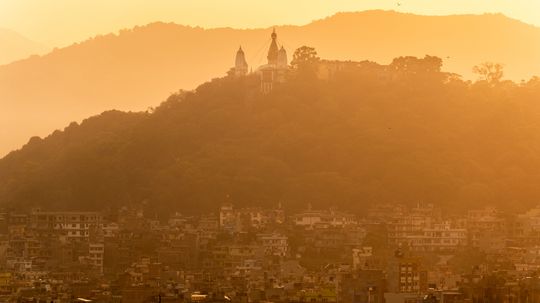

The Worst Air Quality in the World Is in Mountainous Terrain

The World Hits 8 Billion People; Is That Good or Bad?

Quiz: Can You Tell Climate Change Fact From Fiction?

6 Most Futuristic Cities Powered by Renewable Energy

Top 5 Green Robots

5 Things to Consider When Building a Solar-powered Home

Learn More

The Arctic plants that survive near the North Pole thrive in one of the harshest environments on Earth. Extremely cold temperatures, strong winds, snow, and ice limit tree growth and shape unique plant communities across the Arctic tundra.

As you might imagine, the least-visited country in the world is a place most people have never even heard of. Imagine a destination without long lines, crowded beaches, or flashy resorts. That place exists in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and it's called Tuvalu.

If you're wondering what state has the most mountains, it depends on how you define "mountains." Some states have the most named mountain ranges or mountainous land area, whereas others have the outright highest mountain peaks.

Advertisement

As urban populations grow, some cities are redefining what it means to live in the future. The most futuristic cities are more than just skylines; they're powered by renewable energy, connected through IoT technology, and built around sustainability.

Climbers chase records, not just views. And while the most dangerous mountain to climb isn't always the tallest, it is where ambition meets nature's limits.

From ancient amulets to modern engagement rings, different types of gemstones have always caught the human eye.

You might think tropical nations or far-flung archipelagos dominate the list, but when asking what country has the most islands, the answer may surprise you.

Advertisement

Looking to add earthy elegance to your jewelry box? Brown gemstones offer a unique and elegant alternative to more traditional colored gemstones.

Red gemstones bring a bold pop of color to any jewelry collection. From vibrant red hues to deep crimson tones, these stones have captivated wearers for centuries.

Yellow gemstones add a pop of sunshine to any jewelry collection. These stones, ranging from bright lemon to deep golden hues, can suit nearly every skin tone and style.

Pink gemstones blend science and sparkle like few other minerals. Whether you're drawn to the feminine hue for its metaphysical properties or just its stunning aesthetic, there's a pink stone for every style and budget.

Advertisement

Some gems dazzle with rainbow brilliance. Others whisper their power in deep, dark silence. Black gemstones aren't flashy, but they hold serious weight in style, symbolism and geology.

Purple gemstones aren't just for royalty, but their regal vibe is hard to ignore. From ancient talismans to modern crystal "therapy," purple stones have long held a prized place in our jewelry collections and cultural traditions.

Green is one of nature’s most captivating colors, and green gemstones bring that energy into jewelry with rich, varied tones. From deep emerald green to pale green and bluish green, these stones offer unmatched visual appeal.

From deep blue to light sky blue, blue gemstones offer a diverse range of hues that evoke serenity, power, and timeless beauty.

Advertisement

Rocks might look simple, but they tell an ancient story of Earth’s fiery depths, surface shifts and biological processes.

California is known for its beaches and bustling cities, but what really gives the Golden State its rugged charm are the mountain ranges in California.

Europe is a continent of dramatic elevations and scenic diversity, and the mountain ranges in Europe are a testament to that.

From the Arctic Circle to the warm climes of the southern border, the mountain ranges in the U.S. offer some of the most stunning, geologically diverse landscapes in North America.

Advertisement

Spanning thousands of miles across the heart of Asia and Eastern Europe, the steppe is one of Earth's most expansive and ecologically important biomes. These vast, flat grassy plains stretch from Hungary in the west to Mongolia and northern China in the east, forming what is known as the Eurasian Steppe.

With its vivid red waters and stunning surrounding terrain, Lake Natron is one of East Africa's most mesmerizing and otherworldly natural wonders.

Imagine a doorbell — but for fish. In the Netherlands, this eco-friendly innovation is making waves. The fish doorbell, or "visdeurbel," is a clever system created in the city of Utrecht to help native freshwater fish migrate more freely through canals and locks during spawning season.

By Zach Taras

Wind energy is a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, but people still ask: How many birds are killed by wind turbines?

By Zach Taras

Advertisement

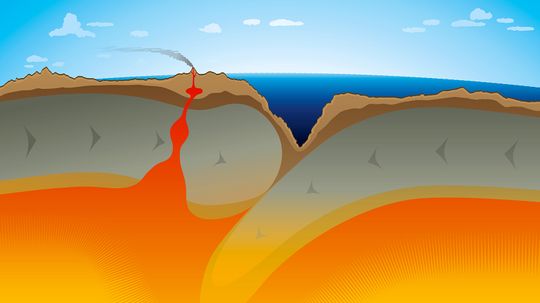

A subduction zone can shake things up — literally. These geological features are responsible for some of the most intense earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis.

By Yara Simón

Air pollution is widely recognized as a major threat to public health, and while air quality data is widely available, the large-scale solutions are often difficult to enact. There are efforts in most developed countries to improve air quality, and pretty much everyone (except the polluters) agrees that it's an urgent problem.

By Zach Taras